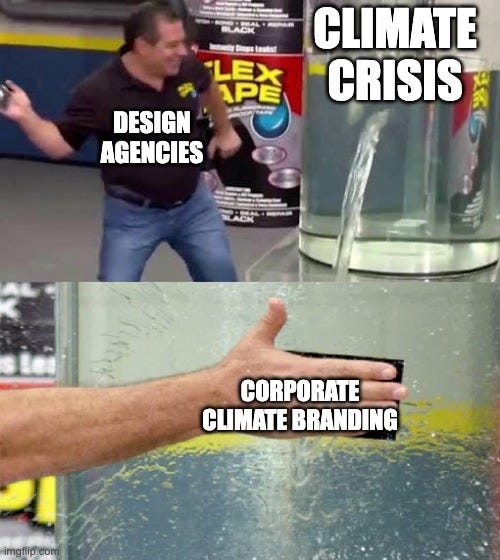

Does ‘climate branding’ miss the bigger picture of systems change?

This sub-category in branding acts like FlexTape on the ruptured water tank of climate change.

Have you all seen this Chobani spot from a few years ago?

It borrows from the “solarpunk” style of futurism that paints a world where humans, technology, and nature are balanced. Robots harvest apples, rain is made at will, and we finally get the flying cars we’ve been asking for. (Apparently, Chobani is also the only consumer packaged good that survived into the future.)

This ad and other climate branding projects that superficially portray sustainable futures put us at risk of entrenching branding as a tool for greenwashing rather than for systemic change. The incentive continues to be 'buy different' instead of 'think different.' “Natural” forms, imagery, and colors are used to sell a lifestyle more than signal values, and graphics are easily appropriated.

While I’m thrilled that nature is going mainstream and the design industry is moving from easily forgotten climate pledges and manifestos to tangible work, recently, the most high-profile projects generally belong to a few categories: carbon offsets, impact VCs, and sustainable materials.

Notably, these industries’ impact prolongs the problems they claim to fight.

Offsets

Carbon offsets allow companies—from tech companies to construction firms, car manufacturers to (incredibly) fossil-fuel producers—to claim they’re “carbon neutral” while, for the most part, continuing with business as usual by simply paying to make their carbon usage ‘go away.’ They offload the work of harm reduction onto other people. To put it another way, it’s hard to claim you’re neat if, in reality, it’s an underpaid maid from a developing country who is responsible for keeping your house clean.

Companies externalize the responsibility (and admittedly hard work) of developing a sustainable worldview and making concrete changes by paying someone else in another part of the world not to pollute. Carbon insetting, on the other hand, internalizes that responsibility.

Impact VCs

As I’ve mentioned before, impact VCs, just like regular VCs, still look for exponential monetary growth in their climate startups, which implies an exponential effort to cut costs, grow margins, and monopolize markets. This tends to create conditions that hurt workers and the environment—something the startups are ostensibly against.

Until VCs change their payment structure, the trajectory of the climate tech startups they fund will be unsustainable because the payment structure demands that.

Sustainable Materials

The last of these industries, sustainable materials, is theoretically valuable, but, in the long term, it’s liable to do more harm than good because of the rebound effect; like with VCs, when the economic objective is growth, any new efficiencies go toward making more growth. So, despite our material and methodological advancements over the past century, we still pollute and work just as much as a century ago.

For material innovations to matter long-term, we need to find another metric for success beyond growth and GDP. In the meantime, material sustainability helps us sell more things people don’t need.

What the companies that finance our branding projects do well is fall into the trap of sustainability as usual: they set unrealistic goals and quickly abandon them when they don’t show profit or can’t charge more for the premium perception that sustainability brings. Despite new sustainability campaigns, AI has caused Microsoft’s emissions to jump 30% since they pledged in 2020 to go carbon-negative by 2030. And despite Nike’s well-branded sustainability initiative, they’ve cut 30% of their sustainability staff (never mind that this initiative set out with the mental gymnastics of doubling growth and halving impact).

By making these ‘solutions’ attractive, I wouldn’t say designers and design agencies are wholly responsible for what amounts to greenwashing, but we can’t, in good faith, claim we’re wholly innocent. Just because we see more sustainability work doesn’t mean corporations consider it anything more than a line item on a list of tactics to increase sales.

That raises a couple of questions: Does climate branding sell sustainability or just the social desire for sustainability—the anticipation that, at last, businesses will put people and the planet over profits? What kind of power does design have when the impact of our work is greenwashing on the scale of unicorns and mega-corporations?

We’ll end up harming more than helping if we continue to craft an attractive, sustainable image for these environmentally and socially unsustainable companies that show zero reluctance to abandon initiatives at the slightest indication of more shareholder returns.

Next Level

If branding—and design in general—is to be genuinely helpful for climate action, we need to look at sustainability with a more holistic lens. We need to stop beautifying and hyping products without looking critically at their social and ecological effects; we need to ensure our work helps change the system rather than sustain the current one.

Cultural, social, and emotional dimensions of sustainability are just as—if not more—important than technology and materials because they’re further upstream. A saying goes, “The most sustainable product is the one that’s never made.” Likewise, the most sustainable design is the one that changes how we think about the world, organize our business, and interact with one another, not the one that uses a bit less ink, plastic, or paper.

A social framing to support our design decisions could help us engage with those upstream dimensions. Thinking about the world we collectively want to experience—as people, not designers—is what Stuart Walker calls ‘appreciative inquiry,’ which

tells us that the questions we ask should be directed toward those conditions we wish to attain.

If we ask, “How can we develop a more environmentally friendly product, such as a car or a clothes dryer?,” we are framing the question in a way that implicitly subsumes a problem—that is, currently available models have a problem that needs to be fixed. By framing the question in this manner, the inevitable result will be a new design concept. Alternatively, we might ask, “How can we live in ways that are attuned to natural systems and facilitate environmental care?”

Addressing this kind of question would result in very different understandings about our priorities, needs, and desires.

A future-oriented design industry shouldn’t ignore finding efficiencies—but it also needs to make deep investments in the big picture. It should value downstream social effects, not just increasing quarterly revenue. But because the questions are broader, they’ll likely require more diverse teams—maybe ones that include anthropologists, sociologists, or geologists alongside designers and strategists.

That might help make a structural change. At least, it has more chance than a fresh logo, mission statement, or plant-based inks would.