🍄 Growth Imperatives No. 3: Unveiling

This week asks the question, "How would we feel about the status quo, if we knew how it really worked?"

This week

🐝 Biodiversity Loss Goes Mainstream

🤖 The Emperor's New Clothes

🫧 Degenerative AI

🐝 Biodiversity Loss Goes Mainstream

You know shit is hitting the fan when the Financial Times is commenting on biodiversity. I loved reading this article because it reveals our dependence on nature in normative, "Homo Economicus" terms.

The TL;DR is that if companies included environmental damage in their costs of doing business, it would wipe out the majority of profits. Not only that, the complexity of nature makes it hard to undo the damage. Sobering stuff.

According to the US Department of Agriculture, pollinators underpin one in every three bites of food eaten on the planet, while the World Economic Forum has estimated that, through everything from water retention to carbon sequestration, $44tn of economic value (more than half global gross domestic product) is “moderately” or “highly” dependent on nature.

Given the accelerating rate of nature loss, the WEF’s figure is alarming. Scientists say that, unless measures are taken to slow the drivers of biodiversity loss, many of the roughly 1mn animal and plant species currently threatened by extinction will disappear within decades. [...]

[B]ecause nature’s costs are not currently being accounted for, companies have a false sense of security, says Paula DiPerna, author of Pricing the Priceless. She compares it with staff costs. “If you could get away with not paying any of your workers, your books would look a lot better,” she says. “We’re getting away with not paying nature, the ultimate worker.” [...]

[W]hile nature’s complexity may leave some feeling overwhelmed, scientists, economists, sustainability experts and others argue that companies and investors must push nature and biodiversity up their list of strategic priorities.

“This is not a corporate social responsibility issue for business and finance,” says Tony Goldner, [the executive director of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures]. “It’s a central strategic risk management issue because the future cash flows of business are dependent on the flow of nature’s services.” [...]

In 2011, the sportswear business Puma did something unusual: by imposing internal accounting measures such as a price per tonne of carbon and per cubic metre of water, it added up the cost of its use of ecosystem services. The resulting “environmental profit-and-loss” account statement was striking. Against that net earnings for 2010 of €202mn, it estimated aggregate environmental costs of some €145mn.

Mandatory environmental profit-and-loss accounting might be some way off, but the risks to business are not. “Every single company is in that situation,” says DiPerna. “People keep investing in companies based on a false sense of their investability.”

Some blame can be assigned to traditional measures of success such as gross domestic product, wrote the University of Cambridge’s Sir Partha Dasgupta in an influential 2021 review of the economics of biodiversity commissioned by the UK government. GDP, he wrote, is “wholly unsuitable” for measuring sustainable development, particularly since “eroding natural capital” is how most nations have achieved economic growth. [...]

As Dasgupta highlights in his review, the degradation or collapse of ecosystems would disrupt the supply chains of many companies, denting their ability to service their debt and increasing their likelihood of default. [...]

[W]hile carbon can be traded globally, nature cannot, says Thomas Crowther, a professor of ecology at ETH Zurich who studies the connections between biodiversity and climate change. “You can’t destroy a tropical forest in Brazil and plant some trees in Scotland,” he says. “With climate change, you suck a ton of carbon out anywhere on the planet and it has a global benefit.”

“It’s a very different case with nature,” agrees Leslie Cordes, who oversees the climate and energy, water, and food and forest teams at Ceres, a sustainable investing network. “Investors are also facing challenges in assessing the nature-related risk in their portfolios because it is so localised.” [...]

Critchlow, the former NatureMetrics chief executive, warns of the dangers of replicating one mechanism used to tackle climate change: carbon credits. While she likes the idea of biodiversity credits generating finance for the restoration of nature, Critchlow worries they could come with the same credibility problems that have dogged carbon markets. “We need much better governance before everyone races ahead,” she says.

Nature’s complexity and regional variation mean biodiversity credit markets cannot operate in the same way as their carbon equivalents, she adds. “There’s no one fundamental price for nature as there is for carbon,” Critchlow says. “And you can’t kill a hippo in one place and save a rhino in another.”

Read: Why nature's future underpins the future of business by Sarah Murray

🤖 The Emperor's New Clothes

Various questions bubble up with the revelation, outlined in this short article, that Amazon grocery stores' ‘automated’ Just Walk Out feature was actually outsourced Indian workers.

What does the design industry risk by diving headfirst into AI, or for that matter, operating with the idea that we need to immediately start experimenting with every new technology? Are we really benefiting from that habit, or is it just an attempt to position ourselves as “forward thinking” to our clients? What do we forego by abandoning criticality and restraint in exchange for efficiency?

The promise of AI, for corporations and investors, is that companies can increase profits and productivity by slashing their reliance upon a skilled human workforce. But as this story and many others show, AI is just today’s buzzword for “outsourcing,” and it comes with the same problems that have plagued outsourced companies and workforces for decades. [...]

The creative accounting techniques that brought us “fast fashion,” off-shore call centers, and even the ill-fated Boeing MAX-C are the very same ones that inspired Amazon to install empty checkout stands fueled by Indian workers whom they expected could do the same work for less. But studies show how outsourcing adds inter-organizational complexity and communication challenges, driving up inefficiencies and decreasing consumer quality. Meanwhile, studies of automation show resulting increases in labor needs and inequalities, requiring both new skilled laborers to supervise the machines and more workers to take up lower-skill roles. As anthropologist Lilly Irani observes, labor is not replaced by machines, it’s merely displaced. While stocks surge upon restructuring, few companies achieve this promise of savings and profitability, and “bullshit jobs” soar. [...]

[T]he future of work is not a technology: it’s an arrangement. An arrangement of people, capital, and workers that moves jobs from where they are expensive and highly-paid, to where they can be cheap and menial. “AI” is a powerful decoy, lest we start thinking about where those jobs have already gone – offshore – and who moved them there in the first place. Because robots aren’t “taking our jobs” – people are.

Read: Don't Be Fooled: Much "AI" is Just Outsourcing, Redux by Janet Vertesi

🫧 Degenerative AI

While the article above talks about the outsourcing problem of AI, the one below talks about its data problem: there's just not enough of it. I see strong parallels between this and the general rule of capitalism, which always needs an exploited party. And because it always needs to grow, it always needs to exploit more.

With AI, this means creating synthetic data to train models on, despite that data's 'degenerative' properties.

As Ed Zitron explains, this—along with market valuations growing like a hockey stick—smells like a bubble waiting to burst. While the hype around AI may be immense, we have to ask if it will end up like the “sharing economy,” which rapidly concentrated wealth and then died quietly.

While the internet may feel limitless, Villalobos told the Journal that only a tenth of the most-commonly-used web dataset (the Common Crawl) is actually "high quality" enough data for models. Yet I can find no clear definition of what "high-quality" even means, or proof that any of these companies are being picky with what they train their data on, only that they have an insatiable hunger for more data, relying instead on thousands of underpaid contractors (with some abroad making less than $2 an hour, a growing human rights crisis in and of itself) to teach their models how to say and do the right thing when asked. In essence, the AI boom requires more high-quality data than currently exists to progress past the point we're currently at, which is one where the outputs of generative AI are deeply unreliable. [...]

One (very) funny idea posed by the Journal's piece is that AI companies are creating their own "synthetic" data to train their models, a "computer-science version of inbreeding" that Jathan Sadowski calls Habsburg AI. [...]

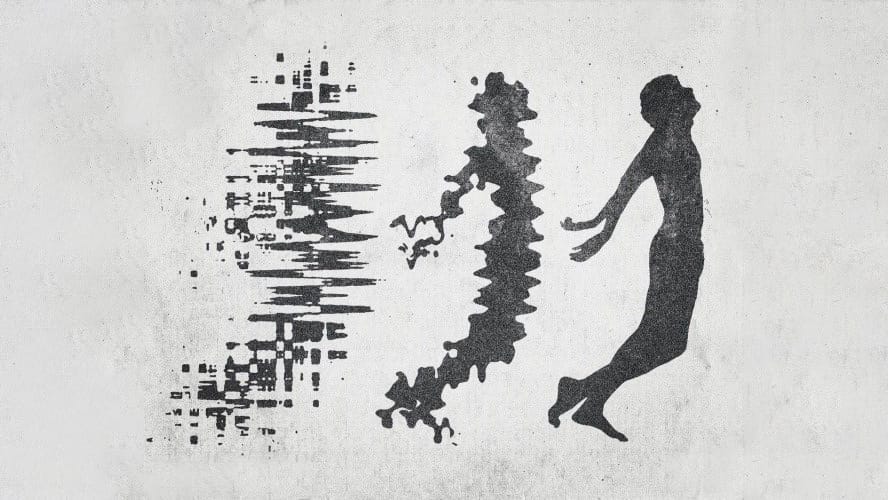

AI models, when fed content from other AI models (or their own), begin to forget (for lack of a better word) the meaning and information derived from the original content, which two of the paper's authors describe as "absorbing the misunderstanding of the models that generated the data before them." [...]

As generative AI does not "know" anything, when fed reams of content generated by other models, they begin learning rules based on content generated by a machine guessing at what it should be writing rather than communicating meaning, making it somewhere between useless and actively harmful as training data. [...]

[G]enerative AI models are prone to hallucinations when using human data. How does synthetic data, created by the very models that need to improve, improve the situation? What happens when the majority of a dataset is synthetic, and what if that synthetic data has within it some sort of unseen bias, or problem, or outright falsehood? [...]

While sources talking to Business Insider claim that GPT-5, OpenAI's next model, is coming "mid-summer" and will be "materially better," there is a growing consensus that GPT -3.5 and GPT-4 have gotten worse over time, and the nagging question of profitability, both for companies like OpenAI and customers integrating models like ChatGPT, lingers. The only companies currently profiting from the AI gold rush are those selling shovels. Nvidia's Q1 2024 earnings were astounding, with revenues increasing more than 300% and profits more than 580% year-over-year thanks to its AI-focused chips, with its next-generation "Blackwell" chips sold out through the middle of 2025. Although Nvidia is yet to announce pricing for the Blackwell generation of GPUs, company CEO Jensen Huang has suggested they may cost between $30,000 and $40,000. [...]

The companies benefitting from AI aren't the ones integrating it or even selling it, but those powering the means to use it — and while "demand" is allegedly up for cloud-based AI services, every major cloud provider is building out massive data center efforts to capture further demand for a technology yet to prove its necessity, all while saying that AI isn't actually contributing much revenue at all. Amazon is spending nearly $150 billion in the next 15 years on data centers to, and I quote Bloomberg, "handle an expected explosion in demand for artificial intelligence applications" as it tells its salespeople to temper their expectations of what AI can actually do. [...]

If businesses don't adopt AI at scale — not experimentally, but at the core of their operations — the revenue is simply not there to sustain the hype, and once the market turns, it will turn hard, demanding efficiency and cutbacks that will lead to tens of thousands of job cuts. [...]

Read: Bubble Trouble by Ed Zitron