Crossing design’s climate skill chasm

The tools, mindsets, and actions that got us here won't get us there.

I have bad news: your design agency is unlikely to solve the climate crisis. At least not through design.

Our individual technical knowledge and the industry’s laser focus on business are only part of what’s necessary for the next generation of design; the world needs more meaningful skills beyond improving efficiencies, making brands grow, and spurring endless sales.

Making design the only lens through which we see sustainable actions creates a situation where a physical output—countless printed objects or tons of data center emissions—is all but guaranteed. But there are other ways to be sustainable apart from our actual design work, like changing the business model of our design studios, incorporating business design into our client work, socializing or commoning resources across the industry, or educating other designers on the changing cultural role of design.

In other words, not everything has to be a one-to-one relationship between us and our visual (or industrial, or fashion) design work.

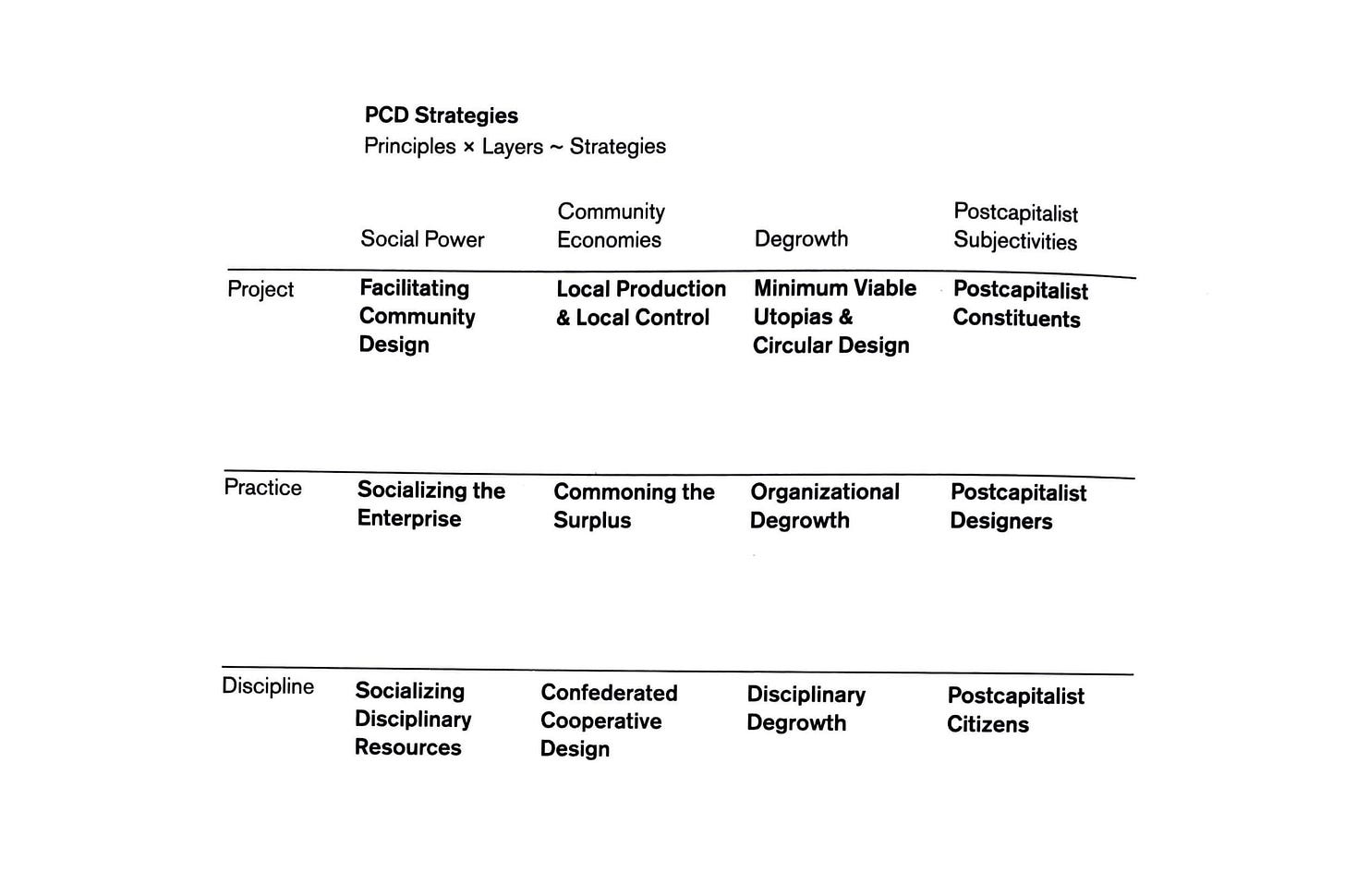

Matthew Wizinsky points out in his book Design after Capitalism that we can act on three familiar levels—Project, Practice, and Discipline—to be more sustainable and erode a capitalist system that serves almost no one. By asking open questions like How might we incentivize collaboration, participation, negotiation, and compromise? on the Project level, or How might we appropriate and distribute social surplus collectively, with and for the practice and its community? on the Practice level, we can think differently about how to make products and how our industry should exist in the world.

Four principles are applied to these three levels: social power, community economies, degrowth, and ‘post-capitalist subjectivities,’ the last two dealing with how to reduce ‘overgrown’ economic sectors and how to imagine ourselves in a post-capitalist world, respectively. These principles give us an outlet to act through design as something besides ‘Designer.’ Acting as Designers limits us to the posters, manifestos, and commercial projects that, as we’ve seen, have little impact or are easily co-opted; it also limits our idea of what’s possible through design.

We must reframe our idea of “Design” and what it means to work in design.

A couple of months ago, on the Frontiers of Commoning podcast, design researcher Safouan Azouzi compared the English and Arabic definitions of “design.” In English—and the Western world in general—the concept of design centers on ‘problem-solving.’ But in Arabic, the word for design, تصميم (“tasmim”), comes from صَمَّمَ (“ṣammama”), which simply means ‘decision-making.’

You could look at the Arabic definition as ‘problem avoiding’ instead of problem-solving, he says.

With this in mind, how much of Western design’s problem-solving has been problem-shifting—to other people, classes, or regions? And how much could we benefit from the wisdom of not trying to solve the world’s problems? Just like at home, we’ll never get to the end of the world’s to-do list; a more novel idea of design might focus on making decisions about current issues rather than being perfectionistic about how the future should be.

In This Changes Everything, Naomi Klein says

Slavery wasn’t a crisis for British and American elites until abolitionism turned it into one. Racial discrimination wasn’t a crisis until the civil rights movement turned it into one. Sex discrimination wasn’t a crisis until feminism turned it into one. Apartheid wasn’t a crisis until the anti-apartheid movement turned it into one.

Right now, the design industry—and seemingly the Western world at large—doesn’t seem too bothered by the change in the climate. To provoke a change, we need to make climate change a crisis. We need movements and ideas to make them bothered and create a crisis worth addressing.

Bridges to cross

What kinds of movements and ideas make a crisis worth addressing?

We can look to social media as an example: until now, the concept revolved around self-contained gardens with extremely high walls. But with the enshittification of basically all networks—but primarily Twitter—the idea of a ‘Fediverse’ or ‘open social web’ has caught on. In the future, through protocols like ActivityPub and AT, you’ll be able to easily take your followers from one platform to another; in theory, this and other improvements should de-shitify the multiple platforms that, at present, seem to actively hate their users. Threads, Mastodon, and BlueSky are built on these technologies, with many more, like Tumblr, WordPress, and Ghost making the transition.

These protocols act as bridges from one internet to another. They’re ideas and actions that highlight long-held and widespread feelings. With climate change, there are a few bridges we need to cross to turn it from an edge case to a crisis. These bridges would, hopefully, lead from the destructive industry we’re currently propping up to a more balanced future one.

Well-being

First, we need to focus on well-being instead of growth. At growth’s extreme, we see people like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. At the time of writing, Musk has $247.2 billion to his name. Bezos has $195.6 billion. They’ve grown (financially) to the highest heights imaginable, but how much better are their customers or employees for it? How much better are LVMH and Inditex’s customers or employees for their high valuations and shareholder returns?

Beyond a certain point, growth is purposeless unless it’s a means to something better, not simply more growth. Like money or technology, using it as the driving ethic for what you do creates a vicious cycle. ‘Enough’ as a principle signifies meagerness and apathy.

If we want to design more in line with nature and to be about ‘problem avoiding,’ we, as people, communities, and industry, need to consider the impact of our designs and hold peoples’ well-being as a core design principle. Unintended outcomes of design—like the addictive effects of infinite scrolling—must be seen as flaws to be minimized rather than trivial side effects to be ignored in pursuit of profits or engagement.

How much of our work—whether your specific job is in communications or landscape design—is ‘calorically empty’ and socially isolating rather than ‘nutrient-dense’ and socially integrative?

Sufficiency

A second bridge that runs directly alongside the first is from efficiency to sufficiency. While growth demands efficiency to make more growth viable, well-being implies you build as much as necessary, not as much as possible. The expansive gap between these ideas gives us room to question how we see the planet, society, and our personal lives—from our conception of nature to our understanding of the purpose of work to how we raise our children.

While efficiency favors the fortunate individuals with access to means, sufficiency favors communities regardless of their means. This naturally creates different types of products, designs, and ideas.

Systemic thinking

Wrapped up in this is a third bridge to cross: a move from reductive to systemic thinking.

I understand why the design industry has so highly valued efficiency and reductiveness. It’s easier to be more efficient than sufficient. Centering sufficiency is messy and complex. Lots of people and consequences to think about. Lots of intersecting systems to consider. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s less productive—just less reductive.

A typical grid-plan city might have wide, straight streets, but it often misses the character of medieval cities or neighborhoods built before city planning was so rigid. A lack of permanent street seating might let people move more quickly through busy streets, but it also prohibits them from stopping to chat. Productivity can be attached to more than a dollar amount.

Maria Farrell notes that

when we simplify complex systems, we destroy them, and the devastating consequences sometimes aren’t obvious until it’s too late. That impulse to scour away the messiness that makes life resilient is what many conservation biologists call the “pathology of command and control.”

The impulse to simplify complex and messy—but thriving—systems stems from our preoccupation with control. But is that a habit that still serves us? Has it ever?

It’s worth examining how many of our social habits were temporary mends that have unconsciously calcified and if those deposits of salt do more harm than good. Maybe modernism and reductivism have reached their end of life. They’re certainly well past their prime.