Does a “business case” for sustainability make sense?

While it's common to see nature as a storehouse for humanity's needs, the next phase of business will likely need to see it as a collaborator.

The idea that there needs to be a “business case” for sustainability—that it has to be economically ‘worth it’ for businesses to be sustainable—sounds like a bad take cooked up in some corporate exec’s corner office.

But it’s true. If you look at it from a human-centered perspective.

Companies must turn a profit, shareholders need to see a return, and the economy has to grow, whether or not there’s any sustainability initiative.

“Business case” is usually a euphemism for ‘cheap enough not to eat into our margins.’ Sustainable materials need to be as cheap as plastic. Sustainable energy needs to be as affordable as fossil fuels. Sustainable production needs to be as inexpensive as sweatshop labor. In other words, for sustainability to be considered, it can’t affect the bottom line.

However, because ethics have market value, sustainability allows brands to be marketed as premium and capitalize on the social desire to have less impact. That’s also why greenwashing exists: brands want the appeal of ethics without doing the work of being ethical. Whether making sustainability the new luxury or lowering the bar for greenwashing, the system is set up to externalize the cost to both people and the planet.

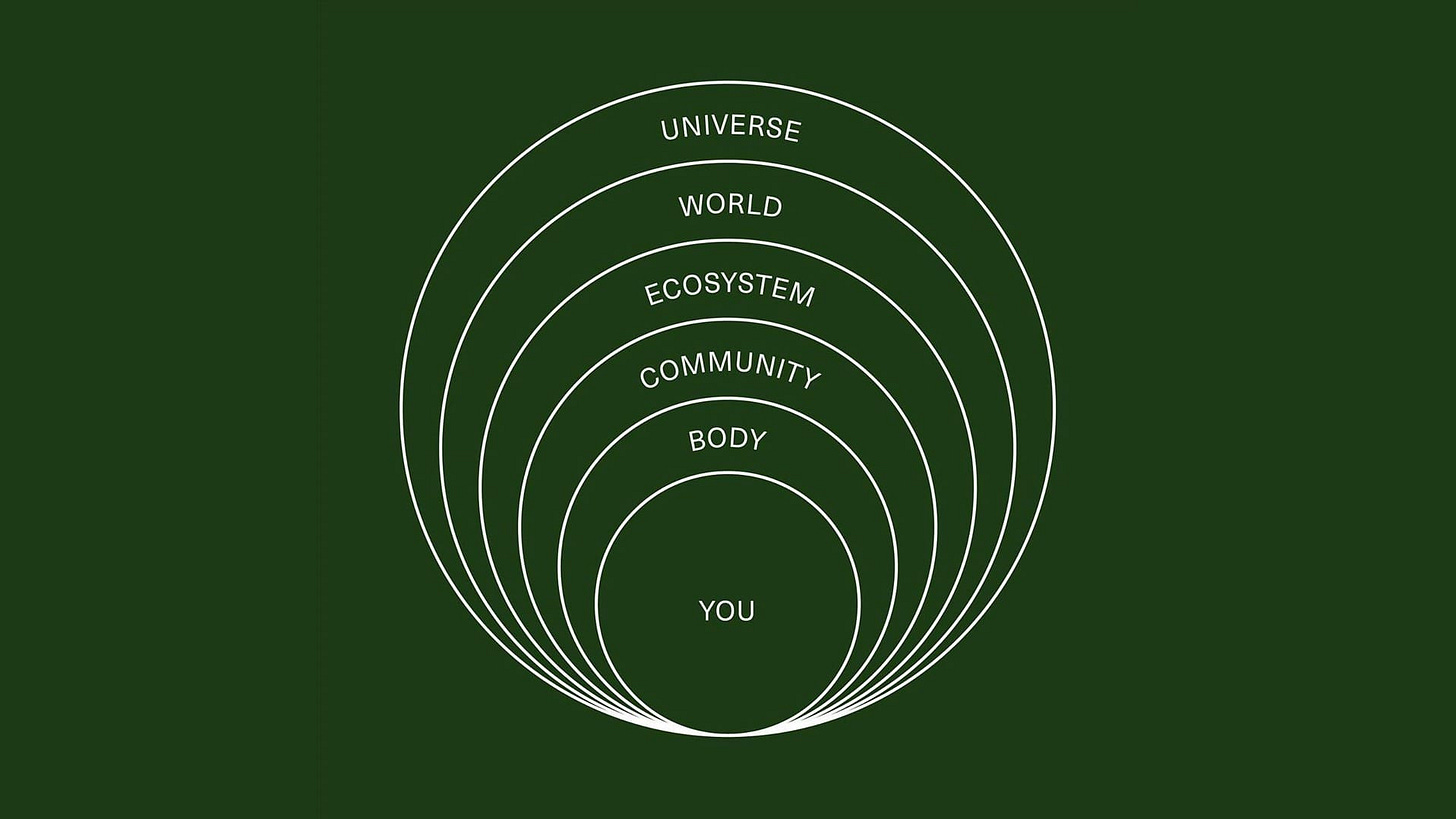

We’re viewing sustainability from a perspective that, far from creating substantial change, centers on incremental changes that keep the machine running. If we flip the polarity and view sustainability from a ‘life-centered’ point of view, we can ask a much more transformative question: “What’s the planetary case for growth-oriented business?”

A global enterprise

I thought looking at this from a business perspective would be interesting. We often judge the planet on what resources it provides to our businesses—why not do a thought experiment reversing the roles? What are we providing to Earth?

COGS

The planet’s “Cost of Goods Sold”—the materials, labor, and so on needed to keep the world’s economies afloat—is astronomical. As I linked in last week’s Growth Imperatives, the global economy relies heavily on nature. Sarah Murray writes in The Financial Times,

According to the US Department of Agriculture, pollinators underpin one in every three bites of food eaten on the planet, while the World Economic Forum has estimated that, through everything from water retention to carbon sequestration, $44tn of economic value (more than half global gross domestic product) is “moderately” or “highly” dependent on nature. Given the accelerating rate of nature loss, the WEF’s figure is alarming. Scientists say that, unless measures are taken to slow the drivers of biodiversity loss, many of the roughly 1mn animal and plant species currently threatened by extinction will disappear within decades.

Ironically, we’re so dependent on nature for our modern way of life—it powers the world as we know it—yet we generally see it as something ‘out there,’ somewhere we go to, instead of something we’re constantly surrounded by. It's to be taken advantage of, at times ridiculed—and rarely has something of substance to teach us.

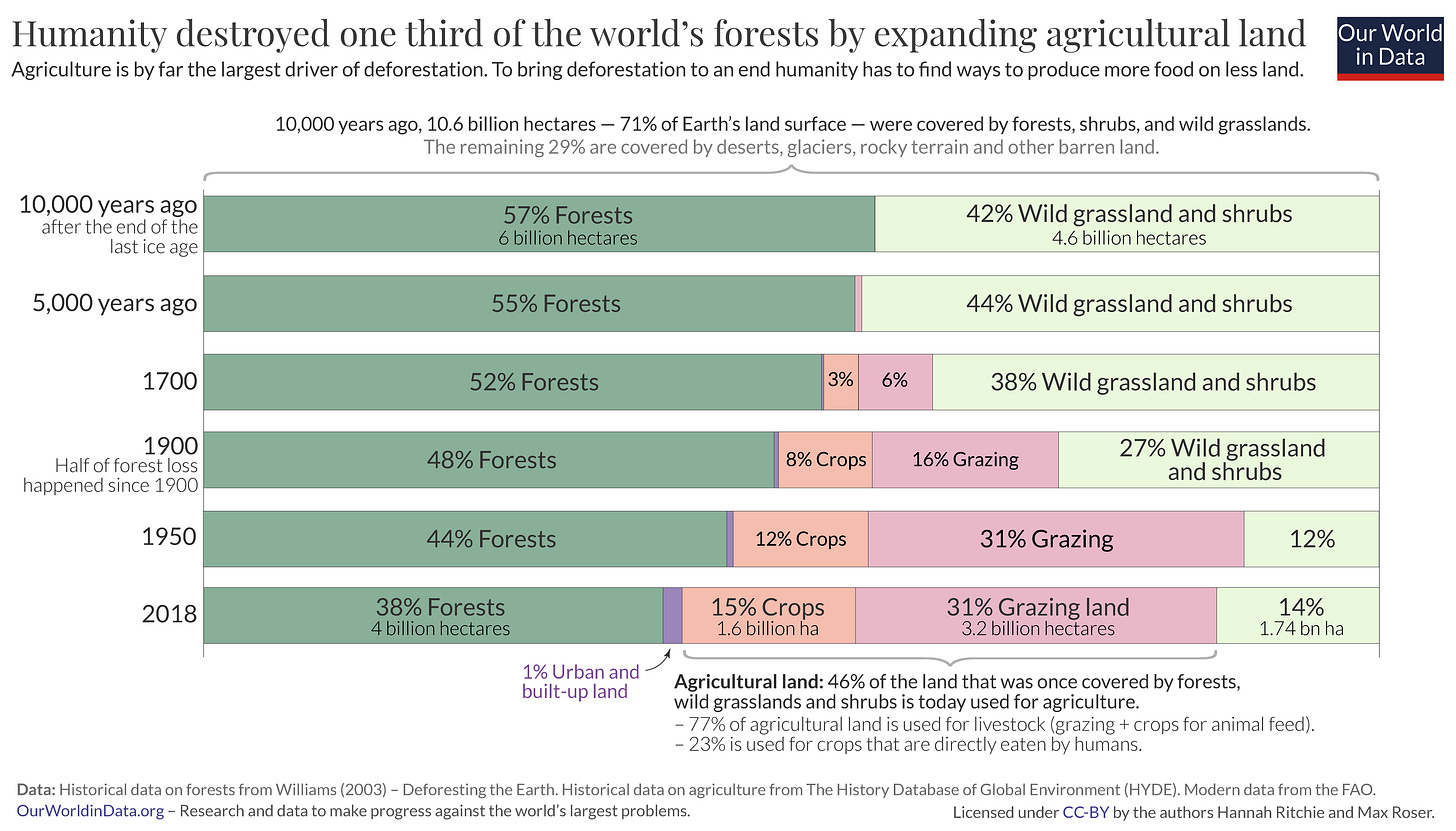

Old-growth forests and grasslands are continually demolished to make way for vast corn, palm, and soybean plantations: 46% of Earth’s entire land mass is now dedicated to agriculture—and 77% of that goes to feed livestock. Flying insect populations have dropped 25% globally since 1990, with specific areas like Germany (75%) and Puerto Rico (98%) showing more population loss. The latter primarily stems from pesticide use on those former forests and grasslands and, to a lesser extent, light pollution in and around towns and cities. Forests and all plant life are essential for carbon sequestration, but many of those plants rely on pollinators—of which bees are only one type, among moths, butterflies, and hummingbirds—to reproduce.

If we don’t remember to place business and economics within the web of life instead of outside, there will be cascading implications for food systems and daily life. A company whose COGS threatens its existence would at least draw questions about restructuring. Or worse, liquidation. Why would that be different when the COGS endangers the planet’s livability?

Profit

Okay, so what about profit—the remainder of revenue minus costs? Is nature seeing returns from business? Humanity is, sure. But the rest of nature? Signs point to a net loss.

Umair Haque sums it up well:

The rest of the world is “producing” stuff — goods — too. Unlike us, though, they are producing goods for everyone, not just [themselves]. Everyone, as in “all of life,” not just “us humans.” Think about the fish. They clean the rivers — from which everything drinks. Or think about the trees — they are happily producing air, which everything breathes. The soil is helping produce plants and other organisms, which are eaten by all kinds of life. The worms clean the soil, which benefits much, much more than just the worms.

Although the ideological trend of the last 500 years has been that we’re the highest form of life, another way to understand the situation is that, in reality, we’re one of the younger species, with various other plant and animal species, like horseshoe crabs and sharks remaining unchanged for hundreds of millions of years. Homo sapiens has been around for ca. 200,000. A life-centered view of the world might see the rest of nature as our successful parent and humanity as its child trying to make a name for itself; growth-oriented business is our latest venture.

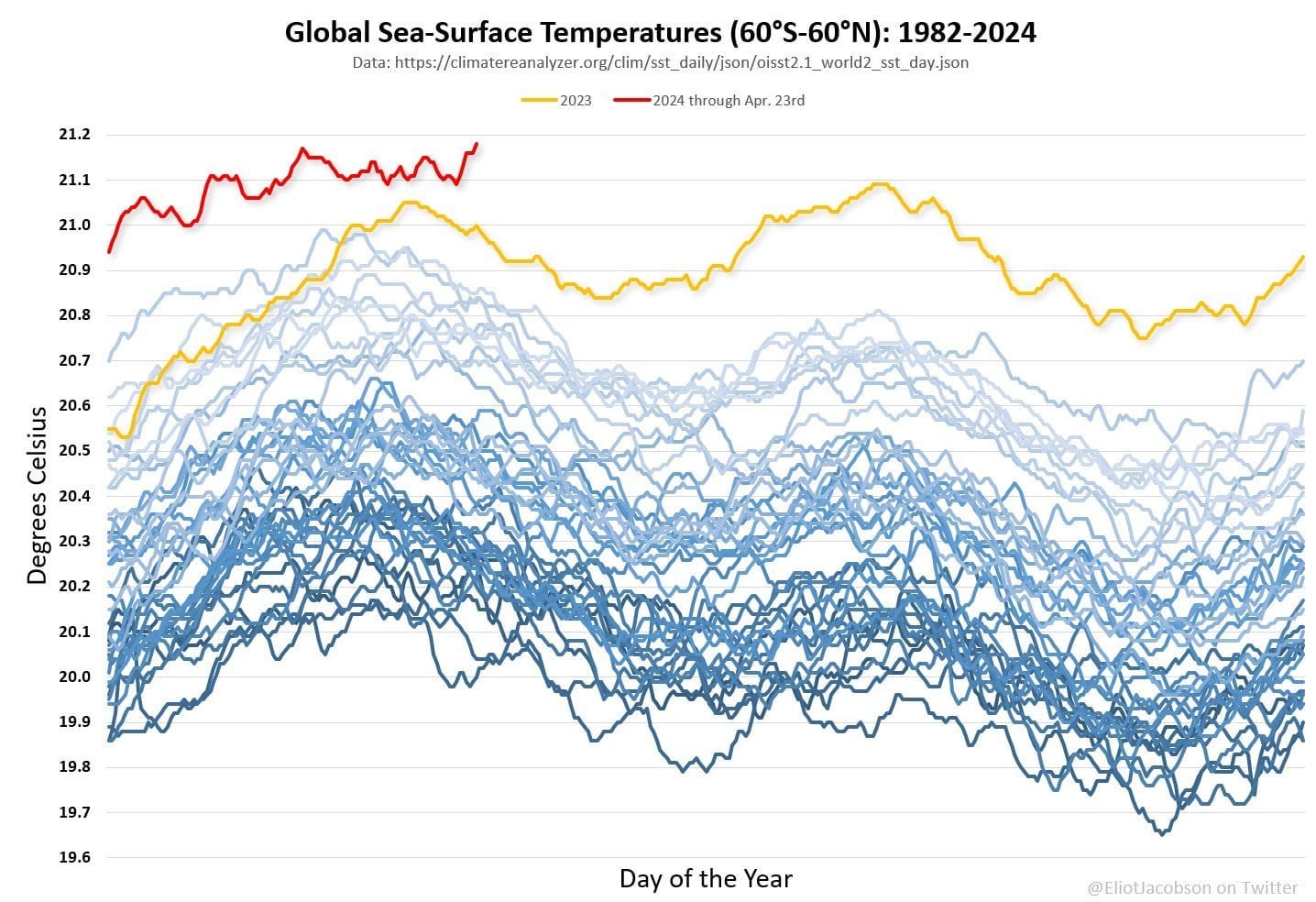

Much of that endeavor is concentrated on taking power, from gaining the maximum rather than giving it. Increasingly, it feels like we need to start giving power to have long-term prosperity. It makes sense. No relationship has ever survived where one party always gives and the other constantly takes. We’re draining our parent’s bank account right now, and we’ll likely be cut off at some point. Looking at recent temperature and biodiversity trends, that may be happening already.

With that in mind, what if we start thinking about our usefulness to the rest of nature, not just ourselves? What if businesses profited not by exploiting more but by empowering more?

Value Proposition

COGS are through the roof, and profit is in the dumps, but does growth-oriented business at least have a strong value proposition? What pains or gains is it claiming to solve?

Progress

Its value is all in the name: “growth.” And who doesn’t love growth? It allows us to reach new places. It pushes us to “think different.” We make ever-longer strides in an ever-shorter time.

But when it comes to economics, growth means something else entirely. Infinite growth demands infinite exploitation—endless ways to squeeze more money out of the same, or worse offering—which is why Uber now costs more than taxis, Amazon has introduced ads into its streaming services while raising prices, and GrubHub makes “mafia margins.” This quest for growth eventually forces everyone to follow the same playbook or be left behind. It’s a hedonic treadmill—a staircase whose top we never reach.

Even Adam Smith—the inventor of the “invisible hand of the market” theory, sometimes called the father of capitalism—knew that growth-oriented economics would eventually become inviable. He thought that “economic progress would eventually come to an end when the wealth of nations had been pushed to the natural limits of soil and climate,” but, according to him, that time was so far off in the future that it was irrelevant.

But that time has come, and it’s very relevant to us.

If you think about it, growth is silly unless it’s a means to another end. As an end in itself, it becomes ridiculous. What exactly are we progressing toward? Forgive me for the cliché, but what other thing in nature grows indiscriminately, except cancer? Everything else reaches a point where stasis is more advantageous than growth, but understanding when that time has come requires a connection to the earth, the self, and others. One that, for us, has atrophied.

Competition

The other half of the value proposition is that a competitive atmosphere provides prosperity, an allegedly organic part of nature that permits us to act on our long-held instincts. But even here, we go against the norm.

I was surprised to learn that nature doesn’t compete unless there’s plenty of surplus. Competition, high resource use, growth, and sprawl are all present in natural systems, but only for a specific time—once scarcity is present, nature switches from competition to cooperation. Society overlooks this transition and twists the basic idea of cooperation in nature.

Take Darwin’s “survival of the fittest.” His original statement says the species that successfully fits into the environment survives—not the strongest or most domineering species. Yet this second reading is what sticks today. The true meaning has been so misrepresented that even in nature documentaries like Planet Earth, the main attraction is the apparent dog-eat-dog nature of the world rather than any collaborative instinct.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, a Potawatomi biologist, expands on this in her book Braiding Sweetgrass:

The key to success is to get more of everything than your neighbor, and to get it faster. That life strategy works when resources seem to be infinite. But pioneer species, not unlike pioneer humans, require cleared land, hard work, individual initiative, and numerous children. In other words, the window of opportunity for opportunistic species is short. …

Industrial forestry, resource extraction, and other aspects of human sprawl are like salmonberry thickets—swallowing up land, reducing biodiversity, and simplifying ecosystems at the demand of societies always bent on having more. In five hundred years we exterminated old-growth cultures and old-growth ecosystems, replacing them with opportunistic culture. Pioneer human communities, just like pioneer plant communities, have an important role in regeneration, but they are not sustainable in the long run. When they reach the edge of easy energy, balance and renewal are the only way forward, wherein there is a reciprocal cycle between early and late successional systems, each opening the door for the other. …

Under conditions of scarcity, there can be no frenzy of uncontrolled growth or waste of resources. The “green architecture” of the forest structure itself is a model of efficiency, with layers of foliage in a multilayered canopy that optimizes capture of solar energy. If we are looking for models of self-sustaining communities, we need look no further than an old-growth forest. Or the old-growth cultures they raised in symbiosis with them.

Trees’ root-bound communication is another example of this “green architecture.” If one is affected by a disease, it can use the root system to alert others nearby, who can then create antibiotics. “Far from being inanimate, [trees] communicate with each other and even share food and medicine through invisible mycelial networks in the soil,” says Jason Hickel in Less is More. Contrary to the norm in modern economics, resources aren’t privatized unless necessary; if they can be shared, they will be.

We understand this on a micro level; a design system works because of its balance, not the supremacy of one element. Somehow, this notion is lost on a social level.

Repatriating business to nature

A life-centered perspective shows the absurdity of a “business case” for sustainability: using it as a business strategy to generate a competitive edge will never create the effect we need. As we see in nature, while competition brings incredible prosperity to some, cooperation generates more abundance by first focusing on sufficiency for all.

How can we build ‘enough’ into business?

The more I learn, the more I feel that the individualism we’ve all integrated can be an inflection point. If the machine was built and survives off weed-like growth, a way out may be to actively reject that growth by organizing differently and finding alternative forms of value. It’s hard to make an exhaustive list of ways to do that in this already-too-long (🥲) newsletter, but I want to talk about one example: “commoning.”

Most of us are familiar with this organizational structure because of the “tragedy of the commons” trope, but it could be a key way to say ’enough.’ Far from being a free-for-all, as is often portrayed, commons are a highly controlled way of organizing that incorporates checks and balances to avoid commodification. A successful modern example of this is Wikipedia.

In contrast to capitalism’s antisocial attitude, where decisions can be made unilaterally, commoning is a consent-based social act where decisions are made by ‘minimum objectionable proposal’ rather than vying for a minimum viable product. Specific methods like sociocracy can help codify this value.

By finding the proposal with the fewest objections, commons define a floor to work from instead of a ceiling to reach. Winner-takes-all decision-making can cause factions to form because it forces those who vote ‘yes’ to fully agree. Consent—leaving room to say that commoners don’t have overwhelming objections and agree enough to move forward—can keep the group on the same page while acknowledging the nuances of disagreement.

It’s a pro-social approach that neatly ties in with the solidarity I wrote about last time. Case in point: Post Office, an explicitly commons-focused business started by designers, intends to transfer ownership of its property to its members as soon as possible. This tactic of decommodifying property is common among commons. In essence, commoning centers on care rather than commerce to create prosperity—a stark contrast with capitalism.

Silke Helfrich & David Bollier write in Free, Fair, and Alive,

The point is not simply to develop economic or government policies that are more “sustainable.” The point is for people to have opportunities to deepen their relationships to natural systems, and in so doing, come to know them, love them, and protect them. ...

“We are of the same stuff” as the world, writes Weber, which is why a walk through a meadow or the arrival of spring causes such delight. Deepening our communion with nature is an indispensable path toward responsible care of the teeming, living world that lies beyond humanity. ...

At its most ambitious, commoning begins a process of re-imagining the terms of modern human civilization at a time when its idealized notion of human aspiration, homo economicus, is revealing itself to be profoundly antisocial, indifferent to democratic norms, and ecologically irresponsible.

If we focus on ticking a box next to “sustainability” instead of creating a deeper bond with nature and each other, we’ll always be at least one step behind where we need to be. Sustainability is a way station in transit from exploitation to regeneration, not the final destination.